Critical Dictionary: An Interview with the Curator

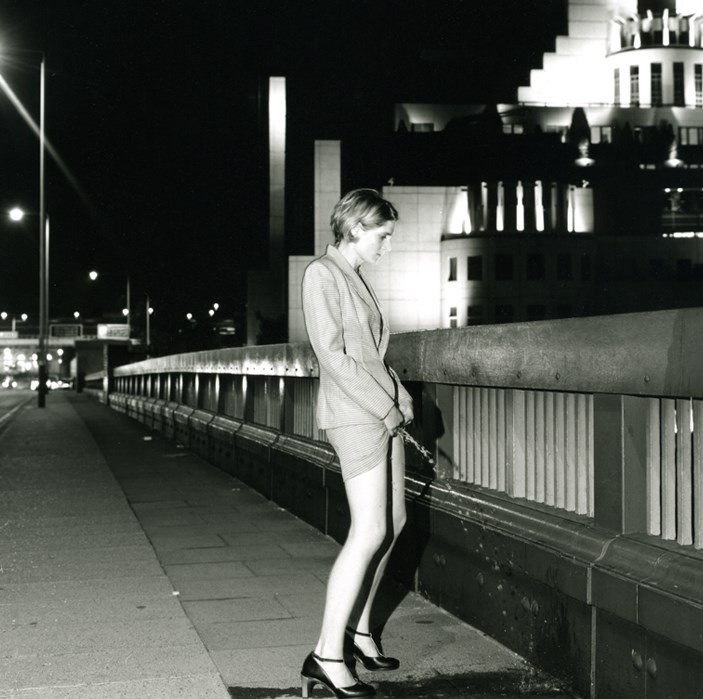

Critical Dictionary is an ambitious cornucopia of words and images from A-Z, questioning common perceptions and standard interpretations of meaning. Part of the artwork has now been turned into an exciting exhibition at WORK Gallery and puts the playful context into material dimension. London Student talked with author and curator David Evans about the inspiration behind Critical Dictionary and its impact on the viewer/reader.

Julia Schell: Is the Critical Dictionary about critical art or critical about art?

Julia Schell: Is the Critical Dictionary about critical art or critical about art?

David Evans: Neither. It mainly presents visual material that queries commonsense understandings of familiar words. Take F for Forest. In the book version of Critical Dictionary (Black Dog Publishing, 2011), this entry begins with night photographs by Tim Edgar that brilliantly evoke Romantic notions of the forest as opaque and mysterious. Next there are Bianca Brunner’s images of wooden platforms for viewing forests that suggest, perhaps, a post-Romantic notion of nature now reduced to light entertainment. Finally, there is the Broomberg and Chanarin shot of The Saints Forest, Israel, with a short caption that informs you that a lot of the tree planting in this country was done to cover up traces of Arab villages that were seized and destroyed in 1948. Cumulatively, I hope, the photographs convince you that a forest is more than a large area with a thick growth of trees.

Why turn an online-magazine first into a book and then into an exhibition?

In the 1980s I saw the Michael Clark Dance Company performing in Brighton, backed by the Slovenian band Laibach. Then in 2008 I had the idea of bringing them together again at criticaldictionary.com. Via Mute Records, I got a contact address for Laibach who allowed me to sample their recent album Volk and supplied water colour paintings that are part of the CD packaging. And I noticed that one of my ex-students – Jake Walters – was doing production shots for Michael Clark. I got in touch and he was pleased to cooperate, too. The issue quickly came together, confirming that the internet is wonderful for making national and international contacts and for getting things going cheaply. However, it lacks the materiality of the book or exhibition.

What is the common language that binds together the words and pieces in Critical Dictionary?

There are a number of historic precedents, like the anti-dictionary that Bataille and colleagues included in Documents (Paris, 1929-30), an experimental journal that was the subject of the fairly recent Hayward exhibition Undercover Surrealism. Or Brecht’s War Primer (originally published in East Berlin in 1955, with an English-language version finally appearing in 1998), mainly photos clipped from newspapers and magazines in World War II and given alternative captions in the form of four-line verses. And détournement – a tactic associated with Guy Debord and the Situationists that usually involved embezzling or hijacking found words and images, and setting them to work in new contexts.

And in what sense can art itself still be critical nowadays?

Since the 1970s, German artist Klaus Staeck has sought to directly service political campaigns and organizations with postcards, posters, and – increasingly – electronic equivalents. Across the same timespan, his contemporary Hans Haacke has also tried to raise political awareness about a range of issues, but mainly operating in galleries and museums. Haacke told me a few years ago that he appreciates what his friend Staeck is doing, but he thinks that the media debates initiated by his own work can have more influence. At this moment, direct action across the world appears to be as significant as events in 1989 and 1968, and there is an obvious demand for rapid documentation and agit-prop graphics. Nevertheless, there is also a role for more reflective visual work. So: Staeck and Haacke and beyond.

How important are words or theoretical concepts for visual arts – can you enjoy the Critical Dictionary without being an ‘insider’?

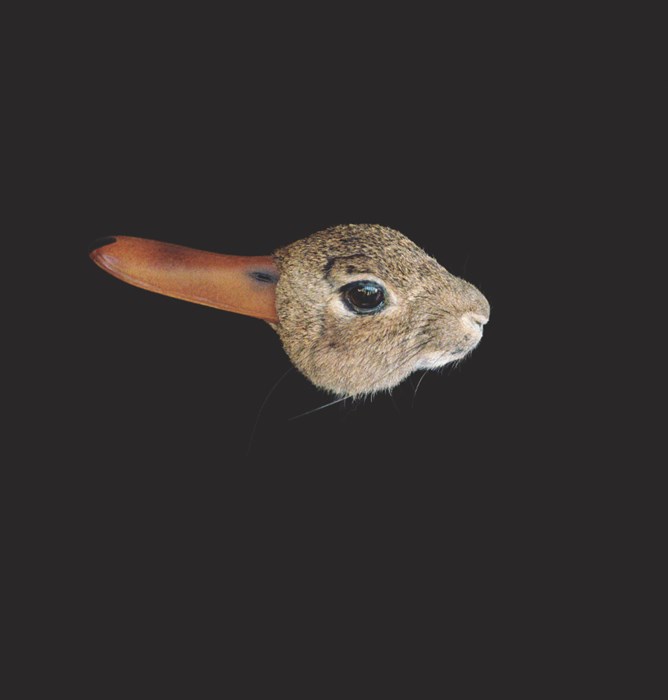

I take it for granted that art is not an exclusively visual medium. As soon as a painting or photograph is accompanied by the label Untitled, for example, then a complex of theoretical issues are raised about the borderline between art and non-art. Such issues are continuously raised by Critical Dictionary, but in an accessible manner, I hope. Like Orwell, it addresses itself to the average sixth-former.

What limits may art test and which borders should it respect, if any?

Critical Dictionary seeks to un-define, to de-classify, but rejects cynical relativism.

David Evans is a Senior Lecturer at Arts University College, Bournemouth, UK. He is Secretary of the online art magazine criticaldictionary.com.

________________

Critical Dictionary at WORK Gallery

27 January to 25 February 2012

www.blackdogonline.com

Back to POSTS!